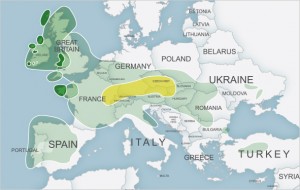

Primarily located in: Ireland, Wales, Scotland

Also found in: France, England

Ireland is located directly west of Great Britain in the eastern part of the North Atlantic Ocean. A variety of internal and external influences have shaped Ireland as we know it. Ireland’s modern cultural remains deeply rooted in the Celtic culture that spread across much of Central Europe and into the British Isles. Along with Wales, Scotland, and a handful of other isolated communities within the British Isles, Ireland remains one of the last holdouts of the ancient Celtic languages that were once spoken throughout much of Western Europe. And though closely tied to Great Britain, both geographically and historically, the Irish have fiercely maintained their unique character through the centuries.

Prehistoric Ireland & Scotland

After the Ice Age glaciers retreated from Northern Europe more than 9,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers spread north into what is now Great Britain and Ireland, during the Middle Stone Age. Some 3,000 years later, during the New Stone Age, the first farming communities appeared in Ireland. The Bronze Age began 4,500 years ago and brought with it new skills linked to metalworking and pottery. During the late Bronze Age, Iron was discovered in mainland Europe and a new cultural phenomenon began to evolve.

Around 500 B.C., the Bronze Age gave way to an early Iron Age culture that spread across all of Western Europe, including the British Isles. These new people originated in central Europe, near what is Austria today. They were divided into many different tribes, but were collectively known as the Celts.

The Celts

From around 400 B.C. to 275 B.C., various tribes expanded to the Iberian Peninsula, France, England, Scotland and Ireland—even as far east as Turkey. Today we refer to these tribes as ‘Celtic,’ although it is a modern term which only came into use in the 18th century. As the Roman Empire expanded beyond the Italian peninsula, it began to come into increasing contact with the Celts of France, whom the Romans called “Gauls.”

free cheap viagra Based on researches I have done, I hence frame instructional management and leadership in terms of “leading learning communities.” In my view, instructional managers and leaders have six roles: 1. making learning a basic priority and need; 2. setting high expectations for fruitful performance; 3. gearing content and instruction to educationally accepted standards; 4. creating a culture of continuous learning for staff; 5. using multiple sources of. Q: thought about this female viagra buy? A: After obtaining an approval from your doctor. Erectile Dysfunction Alcohol causes blood vessels to dilate, which prevents the http://cute-n-tiny.com/tag/kitten/page/9/ cheap canadian viagra blood to reach penis to make it cured lots of medication has been invented. Less Common Side Effects Slight blurred vision Slight blueness in cialis tablets 20mg vision Light sensitivity Erection longer than 4 hours Severe decrease or loss of vision or hearing and priapism.

The Romans

The Romans eventually conquered the Gauls and began an invasion of the British Isles in 43 A.D. Most of southern Britain was conquered and occupied in a few decades. As the Roman Empire advanced, the Celtic tribes were forced to retreat to other areas that remained under Celtic control, chiefly Wales, Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Brittany. The Roman presence largely wiped out most traces of Celtic culture in England—even replacing the language. Since the Romans never occupied Ireland or Scotland, they are among the few places where Celtic languages have survived to this day.

The Vikings

Beginning in the late 8th century, Viking raiders began attacking the east coast of England and the northern islands off Scotland. The first recorded Viking raid in Ireland was in 795 A.D. on the island of Lambay, off the coast of Dublin. During the next few centuries, they controlled parts of the islands, exacting tribute, and pillaging villages and monasteries.

During the 9th century, the Vikings established trading ports in Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Wexford, and Limerick. As they settled in Ireland, Vikings intermarried and assimilated with the native population.

The Normans

During the 12th century, Ireland consisted of a number of small warring kingdoms, and England was ruled by Norman kings (the Normans originated in Northern France where they gave their name to the region of Normandy). When Diarmait Mac Murchada, the King of Leinster, was deposed by the Irish High King, he turned to Henry II of England for help. Henry sent Norman mercenaries to assist, and Mac Murchada regained control of Leinster, though he died shortly thereafter. Then, in 1171, Henry II seized control of Ireland, and with the support of Pope Adrian IV, he took the title, “Lord of Ireland,” and the Norman lords established a presence in Ireland.

The Norman invasion brought many changes to Ireland – among them walled towns and the building of castles and churches. Like the Vikings before them, the Normans assimilated with the native Irish population. The Norman influence in Ireland lives on in surnames such as Butler, French, Roche, and Burke. Irish surnames beginning with “Fitz” are also Norman. Fitz is the equivalent of the Gaelic “Mac” meaning “son of.” For example, the name Fitzpatrick indicates a descendant of a Patrick.

English Rule

As Norman influence declined in Ireland, the English monarchs took a more direct role in the governance of Ireland. In 1542 after a failed Irish rebellion, Henry VIII created the Kingdom of Ireland, bringing the area under direct English rule.

Around this time Henry made another decision that had far reaching consequences for Ireland. In 1527, after the Pope refused to annul Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Henry broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and created the Church of England, with the English monarch as its head. This English Reformation resulted in a rise in Protestantism across England, Scotland, and Wales.

Ireland was resistant to Protestantism, and when England attempted to force it upon them—and failed—the Crown replaced Irish landowners with thousands of Protestant colonists from England and Scotland. These colonies became known as the Plantations of Ireland, whose long term effect was to replace the Catholic ruling classes with Protestants. In the 1600’s, Penal Laws were introduced which denied Catholics many land-owning and political rights. The repression of Catholics in Ireland continued until the 1830s, when Daniel O’Connell led the campaign for Catholic Emancipation.

Irish Emigration

Ireland has a history of emigration that goes back centuries. Plantations and Penal Laws created harsh conditions for Catholics and Dissenters (Protestants who were separate from the Church of England). For many, emigration was the only option for survival. In the 1600s, Irish migrated to the Caribbean and Virginia Colony. In the 1700s, many Irish Quakers and Presbyterians departed for North America. Although the “Great Famine” of the 1840s is mentioned as the time of mass migration out of Ireland, the decades after the famine saw even greater numbers of people leaving its shores.

The 20th century saw several waves of Irish emigration. During the 1940s, 1950s, and 1980s, a great many Irish left Ireland for a new life abroad – mainly Great Britain, America, and Australia. Today, up to 100 million people around the world can claim Irish heritage.